This is a teaching website of the Australian Institute of Dermatology See www.aideducational.com

Friday, September 23, 2011

Introduction

When completed this website will guide you through the basics of skin cancer surgery concentrating on relevant anatomy and informed selection of surgical excision methods based on the nature of the lesion you are excising and where it is situated on the body. This will be the most difficult of these D----- Made Simple websites to put together. Surgical skill is something that is acquired by experience but you need taught well initially or all that happens is you perpetuate your mistakes. Tissue handling and good suturing is not something that can be taught on a website like this. However we can teach you basic principles of lesion selection, the best surgical method of closure, the best patient preparation for surgery to minimise likely problems etc but then it is up to you to go to reputable training courses or seek a preceptorship watching an experienced doctor carry out these procedures and try to learn from what you see. We will try to scour the web for good videos describing surgical techniques but if you can afford it the book by Paver and Stanford called Dermatologic Surgery has two DVDs with over 100 excellent videos which will go a long way to providing you with experience of good surgical technique and closure selections for various areas of the body. See Dermatologic Surgery

The Lesion

If you are working in Skin Cancer Medicine then the first thing you need to learn is how to recognise a significant skin lesion! You need to know all the variants of the common skin cancers such as BCC, SCC and melanoma but you also need to be able to recognise common benign lesions for what they are and benign lesions that may signify an underlying non skin malignancy associated with various syndromes such as Muir Torre. As well as the triumvirate of BCC, SCC and melanoma you will come across lesions such as Merkel cell carcinoma, Atypical fibroxanthoma, Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and other rarer lesions that you also need to know something about. However common things occur commonly so we will start by looking at the various forms of the common skin cancers and then go over the multiple benign lesions that are found on the skin before ending up with the rarities. There is no easy diagnostic algorithm or mnemonic for diagnosing skin tumours. You just have to be exposed to them such that you recognise them and use your dermatoscope!

Look at this YouTube video of the images in Module 1A. You should do this before reading through the text and perhaps again after you have finished the text! To view these videos in high definition you should click the arrow to start then hit pause and change the 360 to 1028 and click the outward facing arrows box next to it to make it full screen. Keep the pause on for a minute to allow enough of the video to download first before pressing play to avoid interuptions when running.Press ESC on your computer to go back out of full screen mode . If you have a slow internet connection it might be better just to view it in the small mode and 360 resolution.

The video below is an overview of the first Module in the Skin Cancer College Australasia's Advanced Certificate in Skin Cancer Medicine and Surgery.

This video is the overview of Modules 1A-D recorded during the first webinar for Module 1

The Site

Skin cancers on the ears, nose, tight sun damaged scalp and fingers are difficult to close without skin flaps or grafts. We will put up videos of suggested repairs in these areas. In most other areas of the body primary excision and direct closure can easily be accomplished if lesions are diagnosed early and are less than 20 mms in diameter.

The Patient

Patient factors are very important in deciding the nature of surgery you will perform or whether to refer the case. Unrealistic patient expectations or unreasonable concerns about scarring are red flags for referral.

Patients who are diabetic, on blood thinners or who readily get skin infections from surgery require pre planning with withdrawal of blood thinners if feasible, prophylactic antibiotics and or post op bed rest particularly for diabetics with leg swelling and impaired peripheral circulation.Look at the videos below on these issues.

Preoperative assessment of the patient is important. You need to know the patient's medical history, especially drugs that might interfere with clotting or the normal healing process. You need to know how they heal. Do they suffer from hypertrophic or keloid scarring? Some people unfortunately develop hypertrophic scars and others develop true keloids. There are certain areas of the body where the risk of developing keloids is increased such as the anterior chest, the shoulder, over the breast area in females and sometimes on the upper back. It is also a problem if you are trying to do surgery across joints. Are they bleeders despite not being on blood thinning drugs? (Check clotting times if not sure!) Do they regularly get wound infections after skin surgery? (Check for MRSA carriage and cover with an oral anti staph antibiotic.) Listen to this exhaustive lecture from MD LIVE on the preoperative patient assessment. It covers the topics mentioned above and then some!

Preoperative assessment of the patient is important. You need to know the patient's medical history, especially drugs that might interfere with clotting or the normal healing process. You need to know how they heal. Do they suffer from hypertrophic or keloid scarring? Some people unfortunately develop hypertrophic scars and others develop true keloids. There are certain areas of the body where the risk of developing keloids is increased such as the anterior chest, the shoulder, over the breast area in females and sometimes on the upper back. It is also a problem if you are trying to do surgery across joints. Are they bleeders despite not being on blood thinning drugs? (Check clotting times if not sure!) Do they regularly get wound infections after skin surgery? (Check for MRSA carriage and cover with an oral anti staph antibiotic.) Listen to this exhaustive lecture from MD LIVE on the preoperative patient assessment. It covers the topics mentioned above and then some!

The Doctor

Every practitioner carrying out skin cancer surgery should train themselves well before starting in the field and should regularly upgrade that training.

The courses of the Skin Cancer College Australasia or The Australian Institute of Dermatology are recommended.

Module 1 Clinical

Need to cover

Excisions

Skin tension lines, Aligning an excision, outlining the lesion and excision margins, local anaesthesia, vertical excision technique, handling bleeding, closing in layers, the importance of everted edges,wound care after excision, topical antibiotics, patients at risk of poor healing, timing of suture removal, complications of surgery and healing,

Curette and Cautery

Conditions necessary for success, lesions suitable for treatment, technique, healing and wound care, complications including scarring, success rates of treatment.

View the video of part of this clinical ModuleSkin tension lines, Aligning an excision, outlining the lesion and excision margins, local anaesthesia, vertical excision technique, handling bleeding, closing in layers, the importance of everted edges,wound care after excision, topical antibiotics, patients at risk of poor healing, timing of suture removal, complications of surgery and healing,

Curette and Cautery

Conditions necessary for success, lesions suitable for treatment, technique, healing and wound care, complications including scarring, success rates of treatment.

Principles of Excisions and Curette and Cautery

If you are going to cut something out, it is important you know what it is that you are cutting out in the first place. Hence, diagnosing a skin lesion is 50% of the task. Once you know what a lesion is, either because clinically you recognise it, or because you have done a biopsy and you have a histological diagnosis, then you can decide on your margins of excision and your technique. It is a good idea to have written patient consent for what you are going to do. For minor procedures eg biopsy excision that is probably not necessary. But if you are going to do a larger procedure that involves a skin flap or a skin graft, it would be adviseable to have appropriate consent forms signed.

Complete this section on suturing techniques by looking at this presentation from MD Live

Preoperative assessment of the patient is important.

You need to know the patient's medical history, especially drugs that might interfere with clotting or the normal healing process. You need to know how they heal. Do they suffer from hypertrophic or keloid scarring? Some people unfortunately develop hypertrophic scars and others develop true keloids. There are certain areas of the body where the risk of developing keloids is increased such as the anterior chest, the shoulder, over the breast area in females and sometimes on the upper back. It is also a problem if you are trying to do surgery across joints.

Are they bleeders despite not being on blood thinning drugs? (Check clotting times if not sure!) Do they regularly get wound infections after skin surgery? (Check for MRSA carriage and cover with an oral anti staph antibiotic.)

Listen to this exhaustive lecture from MD LIVE on the preoperative patient assessment. It covers the topics mentioned above and then some!

Infiltrating local anaesthetic can be made less painful by consideration the underlying skin tension lines.

I will try and put up a picture opposite of skin tension lines. It is useful to have several diagrams showing them in different areas of the body.

When performing a simple excision the first thing to do is to mark out what you think is the outer limit of the extent of the lesion itself and then depending on the nature of the lesion, apply the margins that are recommended for excision. These vary of course with the type of tumour, but in general terms, a well defined nodular BCC can be taken out with 2-3mm margins. An SCC should usually have 3-5mm.

If these margins encroach on significant anatomical structures such as the nose, eye and lip you may have to modify them but take care with infiltrating or recurrent lesions if you are tempted to do this. Local anaesthetic

I virtually always use 2% Lignocaine with 1 in 100,000 adrenaline. There are certain limits to the amount of local you should inject at the one time because of cardiac toxicity from the lignocaine and stimulatory effects of adrenaline. The pain of injection can be minimised by mixing some sodium bicarbonate with your local anaesthetic. If this is not done, then when you are injecting local anaesthetic, inject it slowly. It is less painful when you do this. It is important that the lesion is adequately infiltrated.

Cutting a lesion out is actually quite easy. The local should be infiltrated 10 minutes prior to actually doing the surgery, but unless you have two theatres running it can be difficult to logistically organise this.

Look at this lecture on Local Anaesthetics Reference Only

What about ceasing blood thinners prior to surgery?

Aspirin and Clopidogrel (Plavix) give me more trouble than Warfarin. They affect platelet aggregation and stop the platelet plugs that initially seal a vessel.Vascular muscle contraction is the primary sealer. Clotting factors deposit fibrin on the platelet plug completeing the sealing process.

I think if a patient has just been routinely put on aspirin then you can withdraw it a week or so before surgery, especially if you are doing the surgery around the eyes, or areas where there are lax tissues where hematomas are very likely afterwards. But if the patient is on a medicine because they have had transient ischemic attacks before, or they are on it because of atrial fibrillation then you have to seriously consider the wisdom of stopping their medications!

The newer fibrinogen inhibiting drugs such as Xeralto or Pradaxa are a real problem when doing surgery. I have the patient stop them for 48 hours before any excisional surgery. If you dont they just ooze and you will get serious bruising and increased likelihood of infection.

Once you have adequately infiltrated the lesion and anaesthesia is good, then the important thing is to incise at right angles to the skin surface. This gives you surfaces that are easy to oppose either by subcuticular or external sutures. It is very easy in fact to cut in at the wrong angle and this makes your correct alignment of the wound edges much more difficult. So concentrate on a vertical incision, angle down later into the dermis and fat for a wedge like removal. I generally then use scissors to undermine and strip back the incised tissue , generally at the layer of the fat and above the superficial fascia.

The next important thing is to close the dead space of the wound.

Most larger wounds on the back or the arms do require subcutaneos dead space closure. I usually use interrupted vicril going from the dermis down into the fat layer, back up into the dermis again on the other edge and then closing and bringing the edges together. Some people reverse this and start in the fat layer at one side and end up in the fat layer at the other and hence burying the suture in the depths of the wound. I find this more difficult!

It is rare in my experience to have suture material being subsequently expelled through the wound. Once you have closed the dead space, you can either use a subcuticular dissolving suture to bring the edges together or use interrupted external sutures or a running suture for that matter.Elderly skin can be a problem. Often they have no dermis strong enough to hold deep sutures. In these circumstances you simply have to use large thick external sutures taking a big bite of the surrounding skin and going deep to the fat layer to try to pull it all together and eliminate the dead space.Luckily old people often heal remarkably well despite these large external sutures!

What if the edges are not well apposed?

Wound Dressings

I like dressing with a bit of antibiotic ointment. I like using Chloromycetin. Both because it reduces any markings from the sutures and improves wound healing. There have been studies that have shown that generally antibiotic ointment is not necessary for the vast majority of patients unless it is on the lower leg and people are diabetics or people who have a past history of wound infections. It is rare for patients to become allergic to Chloromycetin. Bactroban ointment can also be substituted. Some people prefer just to use Vaseline. I like my wounds exposed after 24 hours. I let the patient shower and get them to apply the antibiotic ointment then. Other people prefer to have the wound closed with a waterproof dressing and to leave it closed until the patient is seen for suture removal.

Listen to this MD LIve lecture on wound dressings and antisepsis It lasts about 40 mins but you can jump to particular sections using the list on the left when loaded.

When should sutures be removed?

It really varies from body site to body site. Generally on the face sutures can come out between 5-7 days. On the back I generally leave them 10-12 days even where there are subcuticular stitches. And on the lower leg it can be as long as 14 days before sutures are removed again depending on the degree of tension in the wound.

Complications of Skin Cancer Surgery

The classic elliptical excision is best performed ending with 30 degree angles. This leads to easier closure the excision without dog ears developing. If dog ears do develop then they should be cut out. Small dog ears will in fact resolve with time but aesthetically it is better to remove them early on. There are various techniques for removing dog ears but simply elevating the tissue and excising the cone of tissue on either side is the easiest way to allow closure to occur.

The other major complications are infection, hematoma, and hypertrophic or keloid scarring. (On the lower limb another complication is damage to lymphatics with drainage of some lymphatic fluid through the wound for a period until the lymphatics spontaneously close.)

Hematoma formation can be reduced by meticulous attention to hemastasis at the time of surgery, making sure the wound dead space is closed and ensuring that if the patient is on a blood thinning agent, you can reasonably reduce it for a few days before hand. If a patient presents in the first 24 hours after surgery with significant wound edge bleeding then open the wound up and look for the bleeding point and either cauterise it will a hyfrecator or use artery forceps and tie it off. Generally a compression bandage in these circumstances is not enough. It is better to remove the sutures, take the wound down, look at it carefully again for a bleeding point and deal with it. Then re-suture straight away. These wounds are most susceptible to infection when they have been opened a second time.

If a hematoma does develope after a few days and the patient first presents then, you should open and drain it or clean it out and resuture the wound. If however you get a large hematoma then it is more difficult to do this later down the track and sometimes you just have to wait and allow it to be reabsorbed over a month or so.

Infection

Infection usually presents on the third or fourth day with increasing redness around the wound and tenderness, and a serosanguineous discharge. It is important that you have warned the patient that this might occur and ask them to get in touch if they get any symptoms like this. In these circumstances you should swab the wound to determine the nature of the organism but immediately start the patient on an anti staph antibiotic such as dicloxacillin. Generally I like my patients to take antibiotics for 10 days if they have a significant wound infection. It is then also wise to delay removing sutures until the infection is well controlled or there is a risk of the wound separating. Sometimes one or two sutures have to be removed to allow infection to escape and drain away.

Wounds that are particularly likely to get infected are those on the lower legs and in people with impaired circulation or who are diabetic or where there has been an ulcer prior to incisional surgery. A good case can in fact be made for using topical antibiotic prior to surgery in an effort to reduce surface bacterial contamination and hence reduce the risk of subsequent wound infection.

It is probably a good idea to Listen to this lecture on proper antisepsis and try to minimise the risk of infection in the first place!

Post Operative scarring

This is usually a slow process. Generally you get the first sign of a hypertrophic scar around one month, although keloid scars can be a little bit longer before they start to show. An early keloid scar is often itchy as well as being thick and raised. This is because of mast cells which release histamine within the keloid. If you see someone is developing a keloid scar then see them back early and consider injecting some intralesional steroid. Generally I use Kenacort 10 mg per ml strength and inject this into the scar itself, trying to blanche the scar so that it goes white. This indicates that the steroid is in the correct plane. If you inject it under the scar then you are likely to disolve fat tissue and the scar will just sink in rather than flatten out. If a second injection a month later fails to flatten the scar further, then sometimes 40mg per ml Kenacort is necessary to achieve the results. Other means of trying to flatten scars includes the use of a silicone patch which is worn continuously except when bathing or a topical silicone gel is rubbed in to the wound twice daily. (Dermatrix)

Listen to this lecture on Surgical Complications

Curettage and the Electrodessication

Key Points

This technique is useful for small nodular BCCs less than 1cm in diameter especially those occurring on the back. It is also suitable for superficial BCCs up to 2cm in diameter again especially on the back. The technique should be avoided in infiltrating micronodular or sclerosing basal cell skin cancers and any skin cancers occurring in areas prone to deep extension such as embryonic folds as are found on the face and any area where there is a less than firm dermis to allow you to actually carry out the curettage, for example around the eyelids or perioral skin. The five year recurrence rates for curette and cautery are about 25% but much less (around 10%) if used selectively by an expert.

Question What is the anatomical premise behind curette and cautery and how is it carried out?

Answer

The primary premise behind curettage is that the tumour is soft relative to the dermis and therefore it can be easily curetted away to a firm base. This is true for most small nodular BCCs, superficial BCCs and superficial SCCs. The technique for curette and cautery is to stabilise the skin using the thumb and forefinger of the left hand and then to take the right hand with the curette in a pencil grip and scrape the surface of the tumour. Curettes are relatively blunt so they do not cut into the skin. Superficial BCCs and nodular BCCs curette away easily. SCCs often tear away. This feel of soft tissue is more reliable when curetting is done on the trunk and back and less reliable on the face where there is a 12% to 30% residual BCC being left there. Generally several cycles of curetting and then lightly cauterising the surface is carried out though the data that suggests the cauterising improves the removal of any residual basal cell skin cancer is not strong. Also if there is any undermined epidermis at the periphery this should be trimmed away with scissors.

Question Is any skin cancer left behind after curetting?

Answer

Several studies have been done to assess whether any tumour is left behind after what appears to be definitive curettage. In a study by Salashe, residual BCC was seen in 12% of extra nasal lesions and 30% of nasal and paranasal lesions. Another study by Bennett demonstrated residual tumour in about 50% of BCCs on the head but only in about 8% of those on the trunk. However this high residual BCC does not correlate with the recurrence rate and it is possible that the inflammatory response to healing removes residual BCC. Some residual BCC though occurs under the scar and it may be many years before it becomes visible. When these tumours recur on the head and neck it is often as an infiltrative type and may be at the deep margin of the lesions. Spread usually occurs much wider than the scar itself. It is recognised that a relatively benign primary BCC can become a very aggressive secondary recurrence. Recurrence is often multifocal so that the entire treated area before has to be re-excised. The conclusions from most of these studies are that curetting lesions on the head and neck is not a good idea. Curetting them on the trunk provided it is a nodular BCC less than 1cm or superficial BCC less than 2cm is a reasonable thing to do. Curetting a recurrent BCC is just asking for trouble.

Question Should you not therefore just biopsy a BCC, find out what type it is and then decide whether to treat it with curettage or not?

Answer

Unfortunately the histopathology of a non-melanomatous skin cancer is heterogeneous in a given lesion. A study by Maloney reported that 40% of BCCs had more than one histologic type and that 13% of tumours classified as nodular in fact have an infiltrative component.

Question How good are the cosmetic results of curette and cautery?

Answer

On the back the cosmetic results are actually quite good with a small white supple scar. On the face it is a much more difficult situation and surgery is generally recommended in these areas. It is now widely believed that it is best to biopsy lesions first and to treat on the basis of the biopsy other than on long term patients with multiple skin cancers. Some people believe that all biopsies to diagnose non-melanomatous skin cancers should be superficial and mid dermal shave biopsies so that you can still carry out curettage. If you have done a punch biopsy you will have punched right through the dermis.

ELECTRO SURGERY

Electro surgery is the use of electricity to destroy new growths. It can also be used for cutting through normal and diseased tissue with minimal bleeding and of course it can be used to induce haemostasis of small blood vessels. It is divided into various terms and these include electro desiccation, electro fulguration is the other term for it, electro coagulation, electro section, electro cautery and electrolysis.

We are mainly going to use electro fulguration where the needle of the hyfrecator is held above the skin surface and electro desiccation where the needle touches the skin surface. For most of the superficial things that you are going to remove using a hyfrecator in skin cancer work you only need electro desiccation or electro fulguration. (Electro coagulation involves the use of an indifferent electrode and concentrates the current at the point of entry and tends to cause a lot more tissue destruction and we really do not need this for removing most superficial dermatological lesions.) For a spark to be generated with the needle held above the surface of the skin, the skin has to be dry and free of blood. The electrode is held slightly away from the tissue surface and sparking occurs so you get a very superficial dehydration of the tissue. This technique can be used for the removal of seborrhoeic keratoses basically by cooking the tissue such that it just wipes away when you rub it with a dry swab. In electro desiccation say you had the same seborrhoeic keratosis you would be touching it with the electrode and it basically just cooks the deeper layers of the seborrhoeic keratosis. So if you have a thick one you put the needle in contact with it and if you have a thinner one you just hold the needle above and electro fulgurate it. The only other advantage of electro coagulation in dermatology is the ability to seal blood vessels better. So if you have a bloody field then putting the point of the electrode in contact with the vessel, provided you have a plate electrode applied to the lower back, will allow a greater current to go in and may well seal vessels that in a bloody field you would not be able to seal with just a uni polar electrode. Pacemakers Most modern pacemakers really are not affected by the use of these electrical techniques. A defibrillator though may be affected by electro surgery if you are within about 6cm of it so provided you keep away from it or you are not working directly over the underlying pacemaker or defibrillator then it should not be an issue. Obviously if you have a bipolar set up and a plate on the back then you are more likely to get problems than if it is just a uni polar device.

Electro desiccation and curettage can be used for the removal of warts. Again the tip is usually put in contact with the wart to allow adequate penetration of the current in the wart tissue and then the dried up wart can be curetted out. Often you can do a shave removal of an exophytic piece of tissue first to remove the mass of it and then use the hyfrecator to treat the remaining tissue. Some people use this technique for flattening out raised dermal nevi where the nevus is shaved to the skin surface and then the surface is lightly desiccated with a hyfrecator. However I really do not recommend this technique. I think in general you are better punch excising these nevi if you are removing them for cosmetic reasons.

Electro desiccation can be used to treat superficial skin cancers. It is important to remember though those lesions that are not suitable for this treatment. This includes large basal cell or squamous cell skin cancers, including superficial types say over about 3cm in diameter, any morphoeic type BCC, any lesions that involve the nasal labial fold, the oral commisures, external auditory canal and inner canthus of the eye where the lesions can go deeper, any tumour that is recurrent or deeply invasive where there is surrounding scar formation as well would not be suitable for this technique. Also you should not use this technique on any type of suspected melanoma or pigmented lesion where excisional biopsy is the preferred method. When you are using electro desiccation on superficial basal or squamous cell skin cancers remember to treat at least a couple of millimetres beyond the apparent edge of the tumour and to make sure that you are getting any smaller areas that are not visible clinically. We generally talk of serial curettage. What this means is that you do at least two electro desiccations and curettes. Some people would suggest that you actually should do three but I usually find that this is unnecessary. Certainly two are required to adequately treat a lesion using this technique.

Ongoing care of treated area. When you have finished using electro desiccation you are left with a fairly dry eschar. Generally this should be left uncovered and allowed to further dry and separate. Antibiotic powders are usually not necessary and antibiotic ointments do not add much to the healing process. Some people use mentholated spirits as a drying agent but I have an objection to this. Generally the crust will detach within two to three weeks sometimes it will take longer on the lower legs for the crust to separate and it can take up to six weeks in these areas and patients should be warned of this. In general terms with proper selection of tumour to be treated and proper techniques there should be a five year cure rate of over 90 percent in the patients treated with this technique. This technique is particularly useful for patients with multiple tumours particularly on the back, and for elderly patients on the lower leg although the nearer you get to the ankle and the thinner the patients skin the more likely you are to induce ulceration. You do need a bit of dermis to curette against and some elderly individuals may not have this.

The one area that does give some complications using this technique is the scalp where occasionally granulation tissue will develop and it takes some time for it to settle down. Either a topical silver nitrate stick or some TCA can be applied on a weekly basis to reduce this granulation tissue until the lesion heals. Note that some patients though will develop a condition called erosive pustular dermatosis where granulation type tissue repeatedly occurs on the scalp and will in fact settle with the use of a topical steroid lotion such as Novasone lotion applied twice daily.

Electro desiccation over areas such as the anterior chest wall and the sternum or over the clavicles and deltoid regions the patient should be warned that keloid scarring may occur or at least hypertrophic scarring and this complication can be dealt with using intralesional steroid injections.

Electro desiccation and light curettage is also useful treatment of pedunculated soft fibromas, skin tags or acrochordons in the axillae. You do need generally to anaesthetise these lesions with a little bit of local anaesthetic first.

Spider angiomas can also be easily treated using electro desiccation but it requires only a very low setting to obliterate these lesions. They are best treated without local anaesthetic. You simply mark where the central vessel is and apply the needle tip at that point. The other vessels will collapse and settle if the central vessel is treated. You can though treat some of these larger tributary vessels radiating from the central vessels if necessary. For these the hyfrecator is gently moved along the line of the vessel with a linear motion. Sometimes Campbell de Morgan spots on the chest wall can be treated similarly but do require electro surgery in the desiccation mode to dry them out. They may need more than one treatment.

Electro cautery involves a different apparatus with a platinum tipped needle where the needle tip is heated by passing a current through it and this is then used to apply heat to an area and it is useful for reducing blood seepage over a larger area and for sealing any bleeding points after curettage. However a hyfrecator can also be used to take out the small individual bleeding points.

Variants of Simple Excisions

There are several variations of the fusiform ellipse and these include the curved ellipse, the lazy S excision and the M plasty. The M plasty is used where a fusiform ellipse would cross over the border of a cosmetic surgical unit. It is particularly useful if it is going to run toward the lip and cross the vermillion border or near an eyelid margin. Remember that a fusiform ellipse is usually drawn and done along the relaxed skin tension lines. There are various ways to start suturing an ellipse if you are using interrupted sutures. One method is the rule of halves, where the initial suture is placed in the centre of the lesion, and the defect on either side is gradually bisected with further sutures until full closure is achieved. Other people sometimes close the ends of an elipse first to get good closure here, and then subsequently close the rest of the ellipse.

Undermining

Undermining is an important technique used to free up the surrounding tissue and allow it to move easily into the defect. Most undermining should be done at the deep level of the excision to ensure that the base of the defect is adequately closed and there is no space left that could fill with blood or serum. Most undermining is best done with blunt tip scissors rather than with a blade. The scissors should be inserted in a closed fashion, and then opened to break down the tissue along the plane of separation.

A curved ellipse is sometimes necessary to close a defect on areas such as the cheeks. This occurs when you have different diameters of the two sides of the ellipse. It is best then closed by the rule of halves, allowing the two unequal sides to be closed. A lazy S closure of an ellipse creates two curves running in opposite directions. This helps reduce the puckering that can occur on convexities such as on extremities.

An M plasty is generally done to prevent an incision going into a significant cosmetic area and this is particularly an issue at the vermillion border or perhaps the eyebrows. Basically with an M plasty, you create two 30 degree angles at one end of the elipse and this shortens the length of the scar by about one quarter to one third. A three point stitch going through the bottom triangle tip is used to ensure adequate apposition of the tissue.

Healing by Secondary Intention

There are some situations where a wound may be left to heal by secondary intention. This can surprisingly be quite a successful technique to use. It is particularly used on the concave surfaces of the ears, and can also be used even on the medial epicanthus of the eye, provided there is an equal portion of the defect above and below the medial canthal opening. The concave surface of the ear is usually your best bet for this approach.

Listen to this lecture from MD Live on the basic elliptical excision and it's variations described above. Reference Only

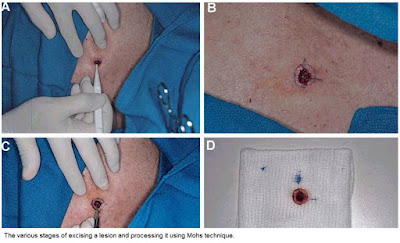

Mohs Surgery, Slow Mohs, Frozen section control by Plastics

Mohs Surgery is used for recurrent and aggressive variants of BCC and SCC occuring in areas of the skin, particularly the face, where tissue sparing but adequate tumour clearance is of the essence. The tissue is incised not at 90 degrees but at 45 degrees sloping inwards. The reason for this is that the edges of the excised disc of tissue are then inked in 4 quadrants and turned down so that the complete outer edges of the disc and the base of the disc are in the same horizontal plane. This piece of tissue is then snap frozen and cut horizontally from the base up. Hence you have a piece of tissue with the base of the excised tumour in the centre surrounded on the outside by the four inked quadrants of the outer edges. Examining this allows you to see if there is any tumour centrally at the base of the excised specimen and the complete outer edges of the excised specimen. The different inked quadrant edges allow you to say where any edge recurrence is and it can then be re excised and processed similarly. By taking several cuts you can minimise the amount of tissue you need to excise to get complete tumour clearance both in depth and at all edges. The conventional vertical breadloafing of excised specimens misses much of the outer tumour edges.

Plastic surgeons who use frozen section control are still having their specimens breadloafed as hence the technique is inferior to Mohs.

Slow Mohs basically refers to excising a lesion one day and having it histologically examined without closing the defect until a day or so later when the specimen has been examined by H/E. Generally these specimens have breadloafing processing as well and hence fail to examine all the excised specimen edges.It is best to not use this term and instead refer to delayed closure after histological confirmation of margins.

Some other information on Moh's Surgery

Below is a YouTube video of Moh's Surgery

When to consider referral of a patient elsewhere

1. Recurrent infiltrating BCCs

2. Aggressive poorly differentiated SCCs

3. Skin cancers involving the external auditory canal

4. Skin cancers involving the lips

5. Extensive scalp lesions

6. Skin cancers with perineural invasion and spread.

As a means of ending this general introduction to excisional surgery you should now listen to this lecture on cosmetic units on the face and how to avoid crossing over them in any excisional surgery you carry out. You will learn the different types of flap closures later on but look at this lecture from MD LIVE as a statement of general principles. Reference only at this stageMCQs for Module 1 Please attempt these before the second Wednesday teleconference for Module 1.

Also complete these Resource Assessment Questions for Module 1. These should be sent in before the second Wednesday Webinar on the Wednesday night. These are graded and count towards your assessment for the Course.

Module 2 Pigmented Skin Lesions and Common Skin Cancers

Melanoma and Nevi

Other pigmented Skin Lesions

Overview of Common Skin Cancers

Other pigmented Skin Lesions

Overview of Common Skin Cancers

Module 2 Clinical Elliptical Excisions

Excisions on the Trunk

Anatomical considerations, Skin tension lines, Skin movement on the back, Problems in healing, Why the ellipse is the excision of choice.

Before you start on this section it would be prudent to Listen to the anatomy lecture from your textbook. This lecture covers a fair bit of facial anatomy. Most of the structures you might be worried about pranging are fairly deep under the underlying facia below the fat layer. Concentrate on those areas where a nerve or vessel lies superficial to the deep facia. eg Superficial temporal nerve on the temple and the 11th cranial nerve in the posterior triangle of the neck.

The Back The first area you are likely to excise a lesion from is probably the back. Lets have a look at some of the problems you might face and how to remove a variety of lesions found there.

Anatomical considerations, Skin tension lines, Skin movement on the back, Problems in healing, Why the ellipse is the excision of choice.

Before you start on this section it would be prudent to Listen to the anatomy lecture from your textbook. This lecture covers a fair bit of facial anatomy. Most of the structures you might be worried about pranging are fairly deep under the underlying facia below the fat layer. Concentrate on those areas where a nerve or vessel lies superficial to the deep facia. eg Superficial temporal nerve on the temple and the 11th cranial nerve in the posterior triangle of the neck.

The Back The first area you are likely to excise a lesion from is probably the back. Lets have a look at some of the problems you might face and how to remove a variety of lesions found there.

Module 5A Histopathology Of Skin Cancer

Part 1:

| |

We will use this module to look at the histopathology of the common skin cancers, particularly in situations where the histology directs the treatment modality or margins of excision. By understanding how tumours grow you can better conceive of why one treatment is better than another.

Other examples of histopathology will be found in the Resources section and links will be found from this module to the relevant parts.

Basal Cell Carcinomas To all intents and purposes BCCs do not metastasise but an infitrating or recurrent bcc is a different kettle of fish from a well circumscribed small nodular bcc. Once you see the histology of these lesions you will understand why! The nodular BCC has sharp edges meaning that clearance by 1-2 mm is fine whereas the infiltrating edges of a infiltrating or morphoeic bcc need 5-7 mm clearance clinically to be 90% certain of removing all the tumour. Have a look at the three cases below.

Image 1 Superficial Multifocal BCC

The superficial multifocal BCC buds off the epidermis. You can see the bluish tumour cells arising from different points of the epidermis with relatively normal epidermis inbetween. Some of these buds may also arise from the edge of a hair follicle. If you look at the outer edge of a bud you will see the cells are arranged in a regular columnar fashion like bricks lined up on the basement membrane. This is known as pallisading and is a characteristic feature of BCCs. This slide also shows some inflammation underlying the tumour. Because of this histology a superficial bcc is often reported as fully excised when the excision site has simply passed between two of these buds through normal appearing epidermis. Many of these buds at the outer edge of a superficial multifocal bcc are so small that they are not visible clinically.

Image 2 Nodular BCC

A nodular BCC obviously has a different look to a superficial multifocal BCC. It is a solid mass of cells advancing as a solid edge. There may still be some peripheral pallisading of cells at the advancing edge. There may also be some separation of the BCC from the tissues it is advancing into. These are called lacunae or tumour spaces.

Image 3 Infiltrating BCC

The infiltrating BCC does not have a solid advancing edge but instead has cords of cells which infiltrate into the surrounding tissues between the collagen bundles. These cords may be quite thin ie only one or two cells thick. They can be far in advance of the presumed clinical tumour edge. This explains why these tumours are often inadequately excised because the apparent tumour edge does not correlate well with the histologically defined edge. Now view these other examples of the histopathology of BCCs

You may find this site useful if you want more information on dermatopathology See Dermatopathology Made Simple

| |

Part 2:

| |

Solar keratoses are really early SCCs with the initial atypia confined to the basal layer of cells of the epidermis. Now most people falsely think that the atypia should be of the upper layer of cells in the epidermis because the sun involves these cells most but remember that keratinocytes originate from basal layer cells and migrate up. The UV damages these basal cells and the damage starts deep. There is also abnormal keratinization from these cells reflected in the thick hard keratin scale on the surface of a solar keratosis.

Clinical correlation You can see that keratolytics will only soften and remove the thickened overlying layer of keratin but do nothing for the atypical layers of cells. Also this thick layer of keratin prevents the penetration of Metvix ( aminolaevulinic acid ) cream in photodynamic therapy (PDT). | |

Part 3:

| |

Keratoacanthomas are rapidly growing "benign" variants of SCC in that they do not metastasise. They have pale coloured glassy cells and a pushing lower edge rather than an infiltrating edge. Nonetheless they are often reported as well differentiated SCCs.

Clinical correlation Many dermatologists simply curette these lesions rather than formally excise them.Because of their pushing edge they usually just shell out. The important thing is to remove them quickly because they can double in size in a two week period. Some can involute on their own but doi not bet on it!

| |

Part 4:

| |

SCC in situ or Bowen's disease.

The keratinocyte atypia extends throughout the whole epidermis from the basal layer to the stratum corneum but is confined by the basement membrane under the basal cells and does not penetrate through into the dermis. Sometimes you see mitoses in some of the keratinocytes. If Bowens disease is secondary to an oncogenic virus then you may see koilocytes high up in the epidermis representing viral involvement. This is common in Bowenoid papulosis on the genitals. Sometimes you will receive a report mentioning an area of Bowen's disease within a seborrhoeic keratosis but this may just be the benign clonal variant of a seb k! Conversely you might get a report of a clonal seb k when in fact it is Bowens disease. This is where your dermatoscope can be very useful. Clinical correlation Because the abnormal cells are confined to the epidermis these lesions can be treated by topical measures including Efudix, Aldara and PDT therapy but note that the wall of the hair follicle is an extention of the epidermis and Bowens disease will extend deeper from the surface in hair bearing areas. Sometimes PDT will not extend deeply enough and recurrences can happen as initial pinpoint lesions ascending up the follicle and spreading into the pale treated epidermis. This can also occur with the other topical modalities including cryotherapy but is least seen with Aldara. | |

Part 5:

| |

Invasive Squamous cell carcinoma These lesions are characterised by epidermal hyperplasia and a thickened sratum corneum. The tumour originates from the keratinocytes in the epidermis but invades through the basement membrane into the dermis. It may do it as frond like masses of cells with a pushing edge but also sometimes as spindle cells infitrating between the collagen bundles.

Clinical correlation An invasive SCC has a more firm base than an SCC in situ. Invasive SCCs are also reported as either well differentiated, moderately differentiated or poorly differentiated. The latter are particularly likely to spread both locally via the lymphatics and around nerves. They require excision margins of 5 mm if possible. Margins of 1-2 mms for excised poorly differentiated SCCs should be regarded as inadequately excised and should be re excised to prevent local recurrence.

Have a look at this video by Dr McColl with Virtual slide technology which looks at actual slides of these conditions. When it runs press pause and the reset the 360 to 720 and click the little box at the side with the arrows pointing out. This will make it display in HD full screen. Press ESC on your computer to revert to the reduced playing size.

| |

Part 6:

| |

The video below lasts about 25 mins. It is a video presentation of a post by Cliff Rosendahl in the SCCANZ Dermoscopy Blog in which he looked at both the dermatoscopy and Histology of benign nevi. Concentrate on the distribution of the nevus cells either on the sides of the rete ridges or also filling the dermal papillae and how this changes the dermatoscopic appearance.

This video lasts 9 mins and looks at a case in the SCCANZ blog with clinical and histological images.

Benign nevi Histologically benign nevi do not show chaos. They have nests of normal looking nevus cells or melanocytes, without mitoses or abnormal nuclei, and show maturation of cells as you go deeper. They are usually well circumscribed lesions. There is a rare variant of melanoma called a nevoid melanoma, seen in younger people, presenting as a rapidly growing dark lesion, which can be misdiagnosed as a benign nevus. It is the commonest reason for pathologists to be sued for missing the diagnosis of melanoma. A Spitz nevus is a benign nevus which disobeys the rules for benign nevi but has some other characteristic features I have outlined in the image below. Dysplastic nevi are clinically atypical nevi varying from normal in size, colour and shape, which show histological features which overlap with those of melanoma especially if classed as severely dysplastic. Clinical correlation The clinical importance of this is that if you excise a pigmented lesion with narrow 1-2 mm margins and it is reported as severely dysplastic, you should re excise to 5mm margins effectively managing it as a melanoma in situ. Have a look at this Jeff Keir SCCANZ Blog Presentation on Close to the Border Line regarding severely dysplastic nevi and melanoma. | |

Part 7:

| |

This video is an overview of the histopathology of pigmented skin lesions.

Viewing this content requires Silverlight. You can download Silverlight from http://www.silverlight.net/getstarted/silverlight3.

Solar lentigo, Lentigo maligna, Melanoma in situ I am not meaning that these lesions represent a progression to melanoma but clinically it can be difficult to decide between these diagnoses especially for larger pigmented lesions on the face. Have a look at the first clinical image below and note the progression of colour and thickness from the lower cheek to the lower eyelid areas. A biopsy taken from each area would show a different histology with an increasing level of chaos. ( The latter concept was first mentioned to me by Cliff Rosendahl who initially applied it to dermatoscopy images.) A solar lentigo is a benign lesion made up of increased numbers of benign melanocytes producing increased amounts of melanin and arranged without nesting along the basement membrane. A Lentigo maligna is an abnormal increase in number, size and shape of melanocytes arranged along the basement membrane in single file or a lentiginous pattern with a little bit of nesting accepted. Often the process extends down hair follicles. Some people also call this lentiginous melanoma or just plain melanoma in situ. | |

Part 8:

| |

Invasive Melanoma Here nests of atypical melanocytes invade both into the dermis and up into the epidermis. The phenomenon of spread of atypical melanocytes up into the upper layers of the epidermis is known as Pagetoid spread and is a feature of superficial spreading melanomas.

Nodular melanomas have little or no epidermal involvement and have a deep dermal component where the cells do not mature as you go deeper. They may also show mitoses and have a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate underneath them indicating an immune attack on the abnormal melanocytes. Desmoplastic melanoma is usually seen on the back with an overlying lentigo maligna like picture and underneath this are spindle celled melanocytes extending deeply into the dermis. They usually feel firm. Beware of shave biopsying these and only getting the upper lentigo maligna like part and hence misdiagnosing the thickness and worse prognosis of these lesions.

The following video looks at a presentation in the SCCANZ Blog by Cliff Rosendahl on the histology of Melanoma.

| |

Part 9:

| |

Merkel cell carcinoma, Atypical fibroxanthoma,Extramammary Pagets disease

Merkel Cell Carcinoma is a small blue stained cell tumour which does not look too bad histologically but clinically has a worse prognosis than a thick melanoma. It is difficult to diagnose clinically even with a dermatoscope but should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any pink rapidly growing nodule.

View this excellent presentation from Cliff Rosendahl in the SCCANZ blog and check out the image link below on the case.

Atypical Fibroxanthoma is another differential of any pink rapidly growing nodule.It is often ulcerated and found on the ear. The histology shows bizarre atypical and sometimes multinucleated giant cells in the dermis with many spindle cells. Treat it like a poorly differentiated SC and excise with 5 mm margins. | |

Part 10:

| |

Special Stains in Histology Some people call these the brown stains or immune stains looking for specific antigens seen in particular tumours. They are useful for determining the cell of origin of say a spindle celled tumour which might be an poorly differentiated SCC or a Melanoma. They are also used in separating Extramammary Pagets disease and Bowens disease in the vulval area and confirming the identity of unusual vascular tumours such as Kaposis sarcoma and angiosarcoma. They can be done on the formaldeyde specimen you sent in initially.

If you want to play with a Virtual Microscope then Try this Virtual Microscope. Click on the button to view a slide in the Virtual Microscope. Concentrate on the skin tumours in this site.Use the + and - function in the little box on the top right side to enlarge the images and left click and hold to move around the image.

These two videos go through some of the images of skin tumours in these sites.

Part 1

Part 2

Modern Genetics in Skin Cancer Diagnosis. View this reference

| |

Module 7A Non Surgical Treatment Options in Skin Cancer

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)